Japan Census

| Japan Wiki Topics | |

| Beginning Research | |

| Record Types | |

| Japan Background | |

| Local Research Resources | |

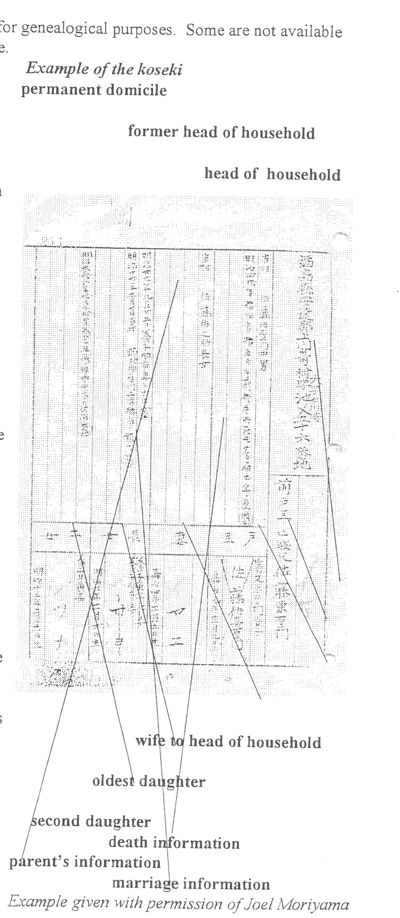

Household Registration Records (Koseki)[edit | edit source]

What they are[edit | edit source]

Koseki is a registration of the population, which is taken nationwide by the government in Japan. This is a compilation of information about each household, including names of all family members. They are regularly updated. When someone is born, married, or died, citizens are required to report it to the village, town, or city record office.

The first one, the jinshin koseki, was started in 1872 and completed in 1873. Distinctions between the nobility (kazoku), the samurai (shizoku), commoners (heimin) and former outcasts (burakumin) were recorded and the registers perpetuated the class distinctions. The jinshin koseki registration system took the domicile or household (ko) as its basic unit. The format for jinshin koseki was standardized in 1886.

In 1898 they no longer recorded the class distinctions. Also, in 1898 legal status was given to the broader, traditional Japanese family. In this system the household (ie) encompasses all individuals within the family who were legally subordinate to the head of the household (koshu) who was charged with the upkeep of all of the family members. Thereafter, this broader sense of household was established as the basic unit of the koseki.

In 1947, after the Second World War, the new constitution abolished the household (ie) system as a legal entity and the koseki law was amended to place an emphasis on the individual. Information in the post 1947 koseki is limited to the nuclear family (husband, wife, and children).

Before the war, wherever the family lived (current domicile) was also considered the permanent domicile. After the war, the place where a family lives (current domicile) was not necessarily considered the permanent domicile. The place where the family lived before the war is sometimes considered to be the permanent domicile.

After a person has died or been otherwise removed from the koseki, the record is considered a joseki (expired koseki). Direct descendants can get these records from the records office in Japan.

Content[edit | edit source]

- Permanent domicile (honsekichi)

- Name and birth date of:

- The husband or head of the household (koshu)

- The wife of the head of the household

- The children of the head of the household

- Parents and grandparents of the koshu (if living in the household) and of the koshu’s wife

- In some koseki, the children, grandchildren, brothers and sisters of the koshu are listed, with their birth dates and places

- Date of household establishment

- Marriage date and place of:

- The head of the household

- Each of his children

- Date and place of death of household members

How to Obtain Your Family's Koseki (Family Registration):[edit | edit source]

Searching for your Japanese ancestors cannot be done the same way you would research for someone from non-Asian countries. The main reason is that Japan has very strict privacy laws and access to Vital Records is carefully protected. That being said, the Japanese are wonderful record-keepers and the koseki or Family Registration is the record on which births, deaths, marriages and divorces of Japanese nationals are kept and is a rich source of genealogical information. A child is listed on his or her parent's koseki until they create their own.

The koseki is kept and protected by the city hall in the hometown (honseki) or permanent address of the head of household. If your ancestor was listed on a koseki, you can get a copy of the record. This is the best resource for finding your ancestors, as often many generations are included. Obtaining your family's koseki requires some effort but it is worth every bit of it.

The best and easiest way to get your koseki is check with other family members, (i.e.cousins still in Japan, etc.) and see if someone already has a copy and will make you a copy. If they do - do the happy dance!

If not, continue with the steps below:

- Make a pedigree chart with all the information you know and determine who was the 1st generation (issei) to leave Japan.

- Locate the address of the honseki or hometown of where your ancestor came from. You will need their address or you cannot locate their city hall. If they came from a large city like Hiroshima, you will need to know the ward or village.You can find this information in several ways:

- Personal knowledge of relatives, written information, correspondense or a copy of their passport.

- Search Passenger List databases on line. A good resource is: http://stevemorse.org/. Sometimes the hometown address is recorded. HINT: Look for other family members who might have traveled with them. Often the husband would immigrate to another country, work for awhile and then come back for his wife - or if he was single, he would return to marry a hometown girl arranged for by his family. Check later years for the family returning to visit relatives and bringing their children to meet the grandparents, etc. Be creative in your spelling as often the names are horribly mispelled. When searching for the wife be sure to use her married name - often you can find the husband by searching for the wife or vise versa.

- Obtain the passport information from the Japanese Consulate (must follow same rules as for obtaining a koseki), though this is often slow and unsuccessful.

- Search the Family History Catalog and view microfilms. Look in the "Subject" catagory under Japan immigration, or just Japan. When searching for information on Passenger Lists try to determine where their first Port of Entry was located. HINT: Do not assume that because they ended up in California that their Port of Entry was in California. They may have first gone to Seattle or Canada. Be very creative and open minded in your searching.

- Once you know the address of the 1st generation (issei) to immigrate, you must check to see if the village or hometown's name is still in existence. Many villages merged into others, names changed etc. Try using google or wikipedia.com to determine the address of the city hall for the town you are searching. HINT: Try www.google.co.jp/ which is the Japanese version of Google if you can't locate it on the English version. You may need someone who can read kanji to translate if the translate version does not work. Most city hall's have a web page and their address is usually located on the bottom of the page.

- Now that you know the name of the ancestor, his estimated birth year, and his address and city hall's information you are ready to contact the city hall.

How to Write City Hall for Your Family's Koseki[edit | edit source]

In order to receive your koseki you will first have to prove your lineage to the person for whom you are requesting. The following information will be needed:

- A copy of your photo ID (Driver's license, Passport, etc.)

- A copy of your birth certificate and a copy of for each set of parents until you reach the ancestor in question. For example, if you want your great grandfather's koseki and he was born in Japan, you would need yours, your parent's on whose line he is on - so if it is your father's line, you would need your father's birth certifcate and both of his parents' birth certificates. You don't need your great grandfather's because his information is recorded on the koseki in Japan.

- A pedigree chart with your lineage written out with information that you have. Highlight the line you are seeking information on.

- A koseki request form filled out. Be sure to use the form provided by your city hall where you are requesting the records.

- Currently the cost for a copy of a koseki and postage is about $15 US dollars per record and depending on the exchange rate. The rate in yen is around 450 to 750 yen. Japanese City Halls will only accept International Money Orders from the US Postal Service. DO NOT send money orders from banks as it will be returned. Make the International Money Order payable to the specific City Hall where your records are located.

- Enclose a self-addressed envelope.

- If you cannot write in Japanese, see if you can find someone who can. It will be most helpful if you write the family's name in kanji, as the characters can be very necessary in distinguishing your family. All Japanese names can be pronounced several different ways, so a request written only in Romanization - containing what you think is the correct pronunciation of the name - may be hard to determine accurately. It is worth trying, even if you don't know the Japanese characters. Try checking with other family members to see if they know it if you do not. If not you can write it in Roman letters, but it will greatly slow things down.

- The City Hall is not required to give you a copy of your family's koseki, even after you prove your lineage. You want to make sure you have everything in order and make it as simple as possible for them to respond to your request. Be patient. It can take a couple of weeks, to many months to receive a response. Any $ change from the transaction will be given in Japanese postage stamps - which you can use again as partial payment on your next request. When you receive your family's koseki it is time for another happy dance!

- It will be necessary to find someone to translate the koseki for you if you cannot read kanji (Japanese character writing). Kanji has changed over the years, so you will need to use the handwriting charts on this page for help. HINT:If there is a kanji you cannot read, download a free language bar from Microsoft. On the Japanese language bar there is an IME pad, using the mouse you can copy the mystery kanji in stroke order and the program will read the kanji in Roman letters. Of course, this is only helpful for someone who knows kanji stroke order.

- Once you have the translated copy of your family's koseki, it is time to input that information onto your Family Group Sheets and Pedigree chart. Using a software program is highly recommended as you will quickly see how complicated Japanese lineage can be because of heir adoptions and name changes. (That is explained further down.) You can use FamilySearch for free or another software program that allows you to type the kanji as well as the romanized names.

Female Lines - Women[edit | edit source]

Women are found on koseki under the male head of household. Usually on a father's koseki until she is married. If her father dies before her marriage it will be under his male heir's name. When you receive your family's koseki you can then request the koseki for your ancestor's wife, as her maiden name, the head of household's name on whose koseki she is found on and the address of where she is from, are all usually recorded on her husband's koseki. This is all the information you will need to now follow all the steps above to now request her family information.

Religious Inquisition Census Records (Shumoncho)[edit | edit source]

What they are[edit | edit source]

The Religious Inquisition Census is a census that was taken periodically to classify people according to their religion and to detect illegal Christians. The government required that everyone register their religious affiliation with the local Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine. Temple priests were required to give this information to local authorities. They do not include samurai. Some kinds of shumoncho are:

- Religion inquisition records (shumon aratamecho or shumoncho for short)

- Individual Surveillance Registers (ninbetsucho)

- Registers of Five-Household Units (goningmicho)

Goningumi registers were compiled to control the population and to deter misconduct within the neighborhood groups. These groups consisted of the five-household unit, which shared responsibility and accountability for each other’s conduct and non-Christians. Time period of the records is 1640—1872.

Record type: A census or population registration prepared on the basis of periodic surveys which classified individuals according to their religious affiliation. There are several varieties of such census records including: Religion inquisition records [shumon aratamecho or shumoncho for short), the Individual Surveillance Registers [ninbetsucho] and the Registers of Five-Household Units [goningumicho]. These can all be classified into one generic category called Religious Inquisition Census Records.

During the 1500s, the feudal lords began counting the inhabitants of their domains as part of their strategy of governance, and in 1644 the shogunate conducted a census [ninbetsu aratame] of its own domains [tenryo]. These censuses were usually prepared by village and town officials upon instruction from district and town administrators. After 1671 there were carried out in conjunction with religious registration [shumon aratame]. The religious registers came into existence because of a Tokugawa government policy which excluded Christian and foreign influences. This registration of the population began in the middle of the seventeenth century and continued until the Meiji restoration with varying degrees of completeness. Except for semiannual surveys of changes in the population of the city of Edo (now Tokyo), censuses were not made on a regular basis until after 1726, when national surveys were scheduled every six years.

The general public was required to register their religious affiliation with the local Buddhist temple or, in some cases, with the Shinto shrine. Temple priests were required to issue attestations of temple affiliation which were then certified by the local civil authority. The ban on Christianity was vigorously enforced. Those who were found guilty of being Christians were forced to apostatize or be put to death. Individual surveillance records [ninbetsucho] and Registers of Five-Household Units [goningumicho] are variations of the shumoncho. Individual surveillance records additionally ensured thorough taxation. Goningumi registers were compiled to control the population and to deter misconduct within the neighborhood groups. These groups consisted of the five-household unit which shared responsibility and accountability for each other’s conduct and non-Christianness.

Time period: 1640 to 1872.

Content: Religious inquisition census records collectively described the make up of the local community, classifying families according to their status as farmers, artisans, merchants, and outcasts. These censuses did not count samurai or court nobles, and they sometimes omitted children and the marginal social groups. Because they were created before the time when surnames were used, they do not include surnames. Shumon-Aratamecho: provide the name of the head of each house and the names of household members; sex, relationship to head of household, age at the time of census, sect affiliation, confirmation of temple affiliation, location of the family temple, number of household residents (sometimes listing of servants, animals owned, and property). Ninbetsucho: give the locality and date of the document created, name of head of household, names, ages, sexes, and relationship to head of household, status of household members; animals owned, property and tax notations, and the amount of taxes paid. Goningumicho give the names each of the five household heads and the chief of the group; locality, date, the temple seal attesting to religious orthodoxy; sometimes names household members.

Population coverage: Originally covered between 80 and 95% of the population. However, less than 12% of the original records still exist. These cover only about 10 to 15% of the population.

Reliability: Religious Inquisition Census Records are considered to be very reliable and have been used extensively by historians and demographers.

Research use: These records identify members of household units. This is unlike the kakocho, which reference specific vital events but provide only sketchy family relationships. This difference is quite significant since during the Tokugawa period commoners were not allowed to have surnames, the key identifier of lineage in most genealogical research.

Accessibility: There are few complete collections in one location. These records are not easily accessible to the general population but scholars often have access.

Location: Scattered in archives, private collections, in the homes of descendants of village headmen, and even in some Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. They must be searched out.[1]

Use these records to[edit | edit source]

These records are used to find the names of the head of the household and family members. Because they were created before the time when surnames were used, they do not include surnames.

Content[edit | edit source]

- Describe the make up of the local community

- Classify families according to their status as farmers, artisans, merchants, and outcasts

- They do not count samurai or court nobles, and they sometimes omit children and the marginal social groups

Shumon-Aratamecho:

- The name of the head of each house and the names of household members

- Sex of each household member

- Relationship to head of household

- Age at the time of census

- Sect affiliation

- Confirmation of temple affiliation

- Location of the family temple

- Number of household residents (sometimes listing of servants, animals owned, and property)

Ninbetsucho:

- Give the locality and date of the document created

- Name of household

- Names, ages, sexes, and relationship to head of household

- Status of household members, animals owned, and property and tax notations

- The amount of taxes paid

Goningumicho:

- Give the names of each of the five household heads and the chief of the group

- Locality, date, the temple seal attesting to religious orthodoxy

- Sometimes the names of the household members

How to obtain them[edit | edit source]

About 30 percent of the still existing records are available at the Family History Library. Because they are scattered in archives, private collections, in the homes of descendants of village headmen, and even in some Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, you must search them out.

Privacy laws, and 80-year retentions restrict access to koseki.[2]

Religious Inquisition Census[edit | edit source]

A Religious Inquisition Census was taken periodically to classify people according to their religion and to detect illegal Christians. The government required that everyone register at their religious affiliation temple or Shinto shrine. Temple priests were required to give this information to the local authorities. They do not include Samurai. Some kinds of census records are:

- Religious Inquisition Records

- Individual Surveillance Registers

- Registers of Five-household Units

Use these records to:

Find the name of the head of the household and family members. Because they were created before the time when surnames were used, they do not include surnames.

How to find these records:

Many of these records are on microfilm at the Family History Library. These records are written in old Japanese, so being able to read and search them you will need a knowledge of written Japanese and as well as a good kanji dictionary that will be necessary to decipher them. In order to find these records in the FamilySearch Catalog, it will be necessary to use the language bar on the computer and type in the Japanese characters under the "Keyword" tab to locate these records in the catalog.

Resident Registration (Juminhyo)[edit | edit source]

Record type: Resident Registration.

Time period: 1870 to present.

Content: Surnames and given names of residents, birth dates, relationship, sex, permanent domicile, present address, date of move-in or move-out, origin place or destination, death date.

Location: City, Town, and Village offices.

Population coverage: Nearly 100% for the time period covered.

Reliability: Excellent.

Research use: Can be used as a substitute for koseki. Resident registration is a primary source of birth, marriage, and death information in Japan. They identify names of parents, prove other relationships, and are very useful for linking generations.[1]

Websites[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Family History Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Family History Record Profile: Japan,” Word document, private files of the FamilySearch Content Strategy Team, 1986-2001.

- ↑ Dr. Kin-itsu Hirata and Dr. Greg Gubler, "Family and Local History in Japan. Breaking the Impasse: Sources and Options in Japanese Family History Research," World Conference on Records: Preserving Our Heritage, August 12-15, 1980, Vol. 11: Asian and African Family and Local History. FHL US/CAN Book 929.1 W893 1980 v. 11

| ||||